Remembering César Chávez, the Delano Grape Strike and the Needs of Today’s Farmworkers During the Pandemic

Born to a migrant farm working family in a barrio of Arizona, César Chávez weathered through a life of deprecation and racism in every aspect outside of his own home. By the time he grew up in the 1930’s, schools were still segregated and he was living in a white man’s world. After the education system failed to support or inspire him, he took to the fields to help his father keep a roof over their heads. For his entire life, Chávez and his family had to struggle to get by, and the only possible way out of the barrio was by becoming an education or serving in the military.

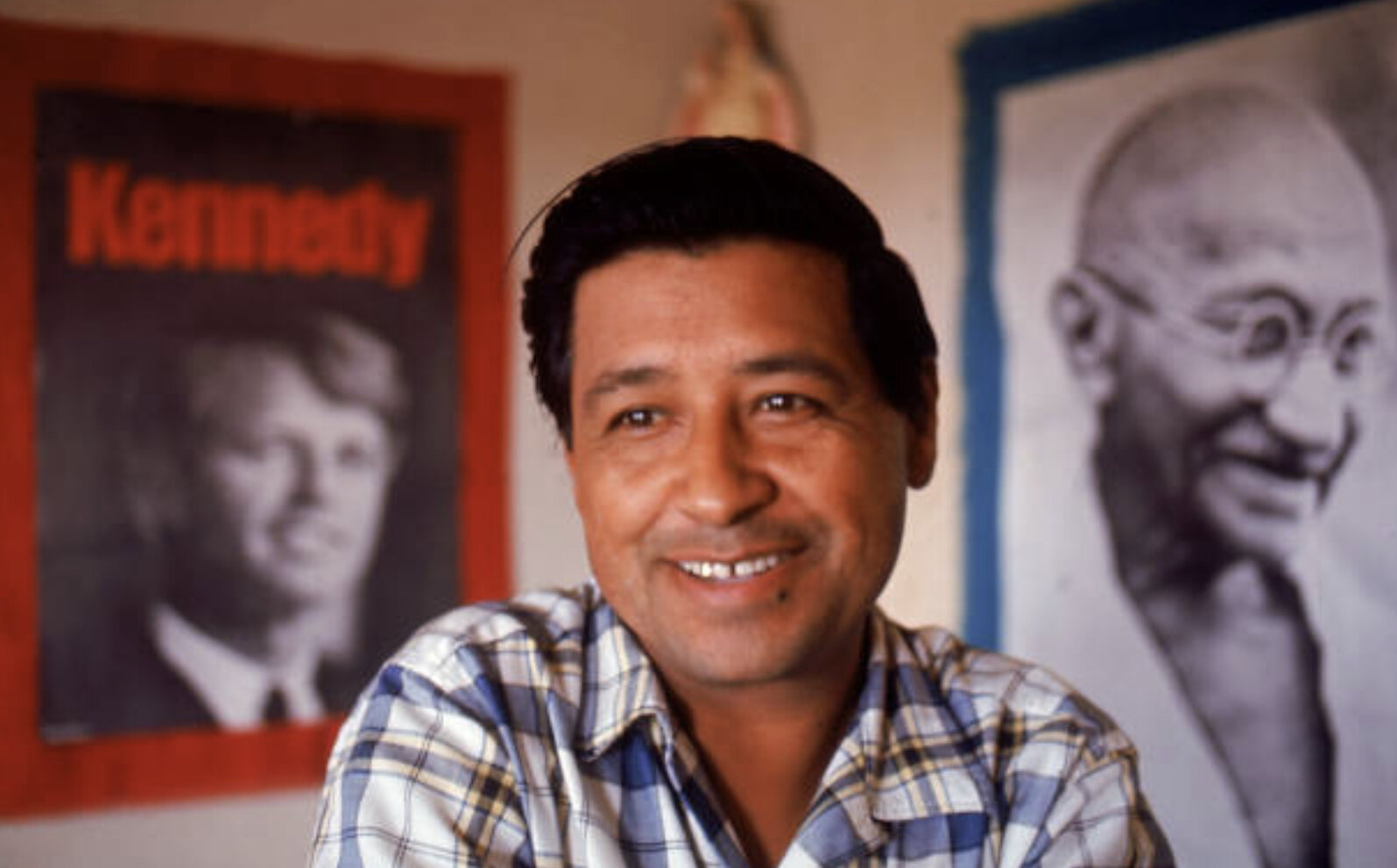

Chávez joined the U.S. Navy, where he served for two years in a still-segregated unit. In his post-grade-school life, he took to the books. Chávez filled his own library with titles from economics to philosophy, reading up on the nonviolent practices of people like Gandhi and St. Francis.

It was after he married his wife, Helen, and started a family that he went back and visited the California Missions along the coast where had honeymooned years before. In San Jose he met some very influential workers rights advocates like Father McDonnel and Fred Ross, who got him to join Ross’ Community Service Organization (CSO). His position was a registrar to help farm workers vote, all along seeing the inequalities throughout the voting system and within the farm working community.

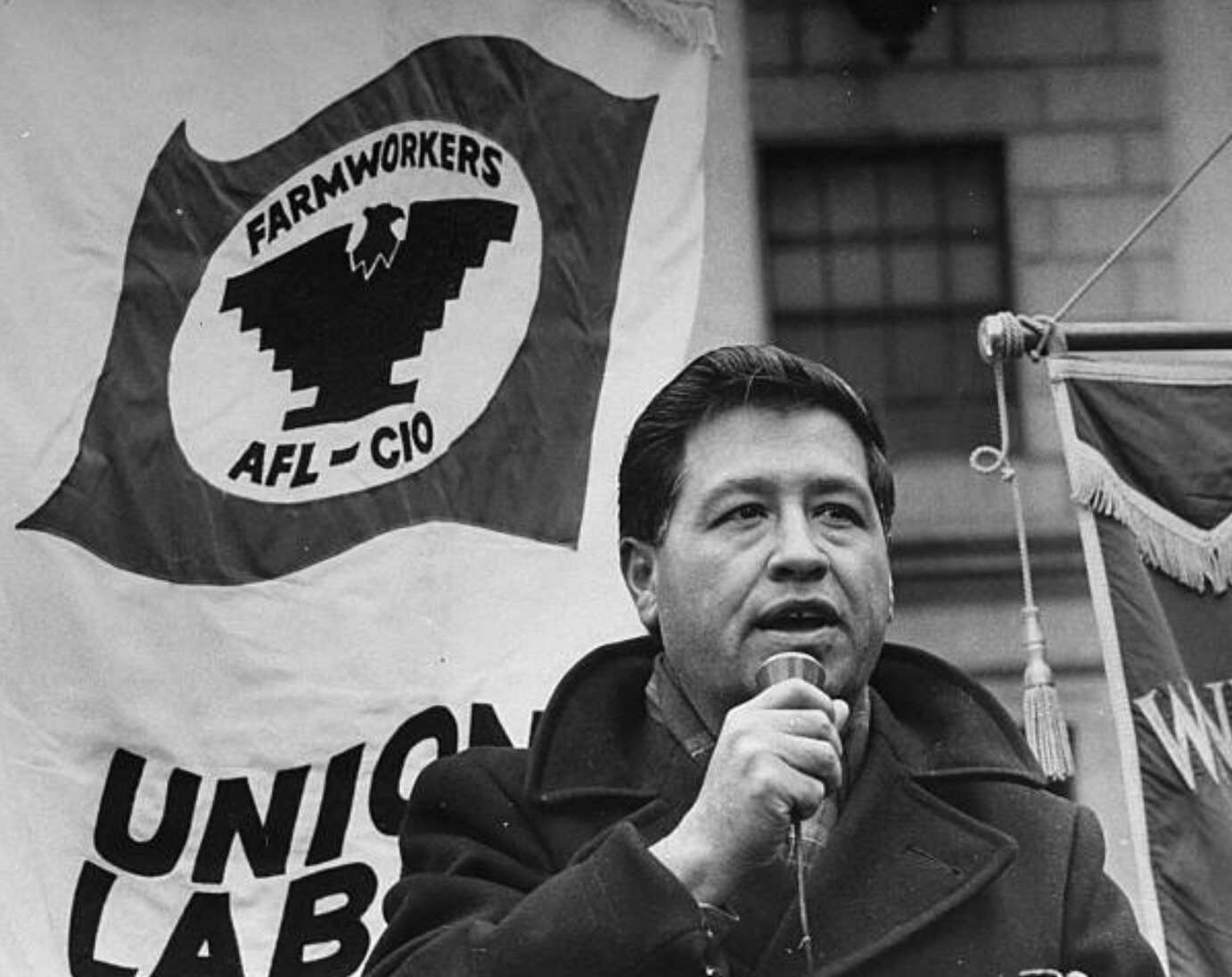

From there, Chávez began a long career in social justice, carrying on the nonviolent practices that were encouraged by Martin Luther King Jr. He co-founded a coalition of Mexican American migrant farm workers with Dolores Huerta, who would be known as the more charismatic and organizationally skilled of the two. Their coalition, the National Farm Workers Association, became United Farm Workers (UFW) when they joined forces with Filipino farm workers that had walked off the job at the Delano grape fields due to poor working conditions and low wages.

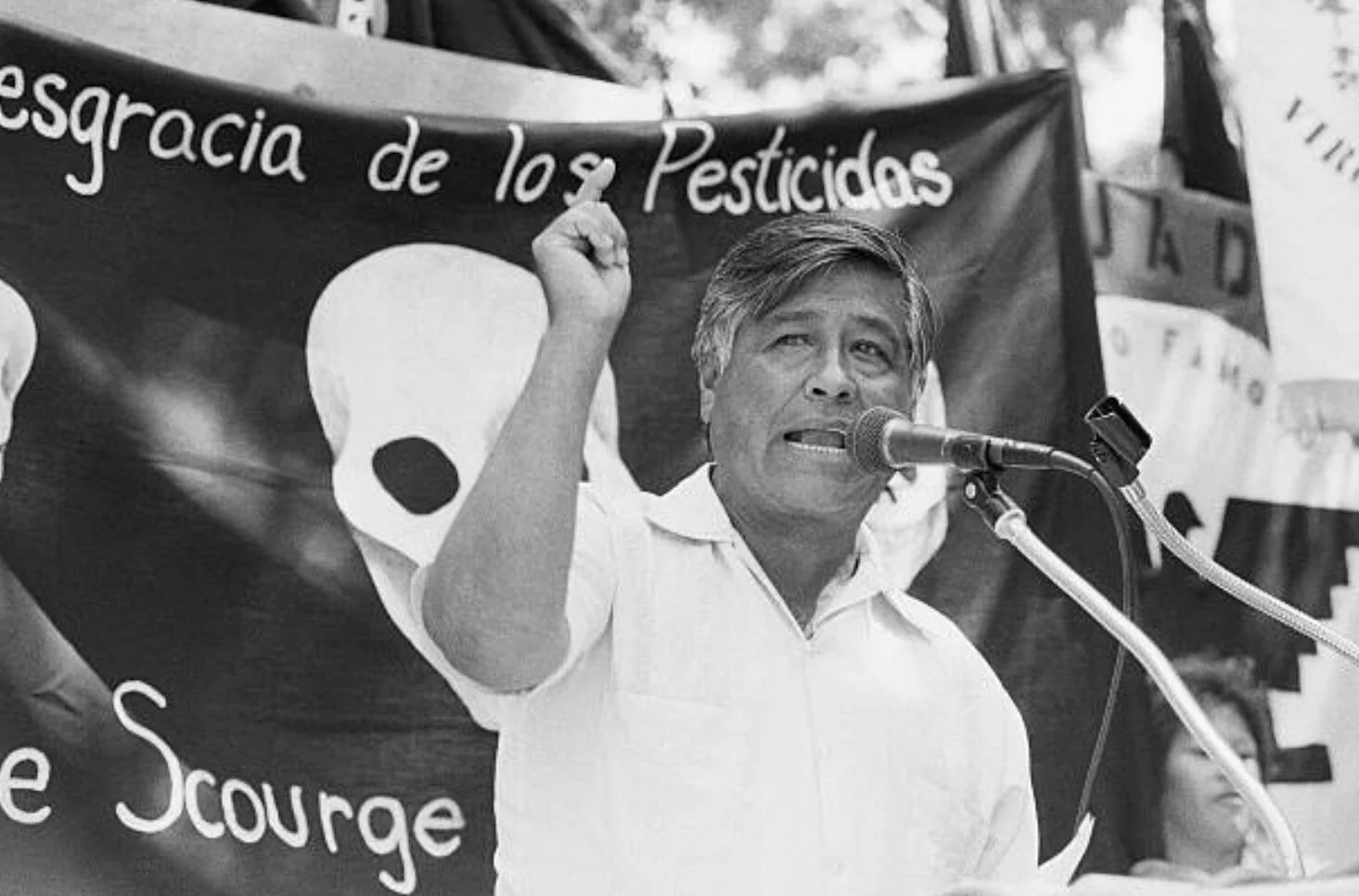

With these new forces as one union, Chávez led the way with nonviolence. He inspired thousands of workers and citizens to join La Causa, or The Cause, in peaceful protests and boycotts of different crops. As Chávez had said, “the fight is never about grapes or lettuce. The fight is about people.” He continued to demand livable wages for farm workers and conditions that didn’t involve directly exposing them to harmful pesticides.

All throughout the 1960’s and into the 70’s, La Causa was about preserving human dignity in the workplace using peaceful protests, which were often met with violence from the American government. So to follow in the path of great nonviolent protestors, Chávez most famously led the Delano Grape strike of 1965 in the form of a 300-mile march to Sacramento, followed by boycotting grapes, as well as the first of his few personal fasts. His perseverance eventually won workers the right to unionize in 1970, as well as grape growers agreeing to sign workers rights contracts.

Unfortunately, Chávez took a toll for the long, frequent fasts he used as a tactic to gain political attention from legislators and producers. He grew weaker over the years, and after winning his last battle against a lettuce grower over workers rights in 1993, it is known that Chávez passed away in his sleep.

His legacy lives on as we strive for social equity in the workplace today. During COVID-19, farm workers have faced conditions that have left them vulnerable to the virus, while at the same time low enough wages that could leave them debilitated if they got sick. Now, just as much as Delano grape workers needed in 1965, we must value our food producers like they provide the essential work that they do. In the spirit of his nonviolent leadership and humility, let us honor our essential workers by choosing to support fair operations and continuing to fight for social justice.